By Amy Fleming

From Issue 27, June 2017

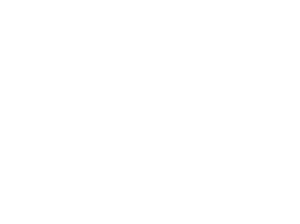

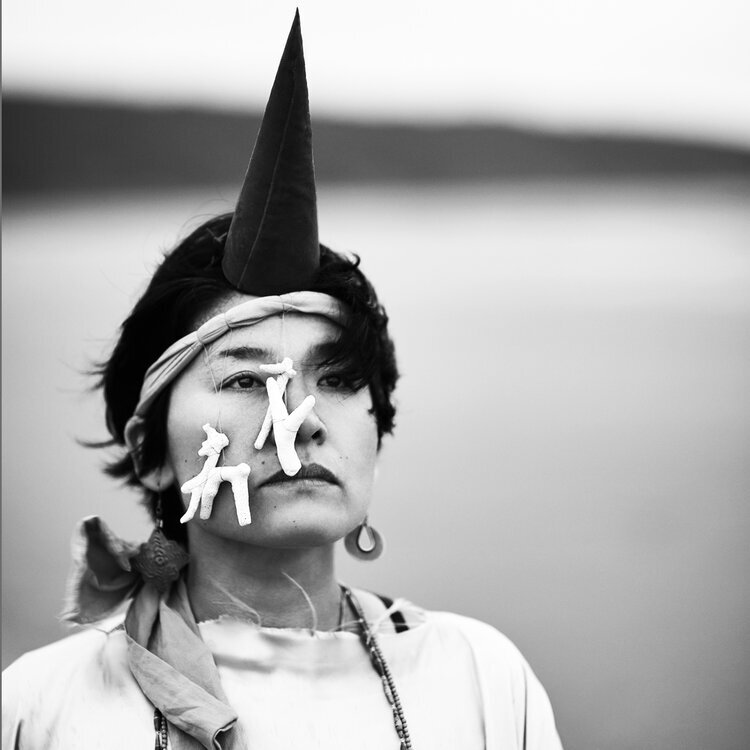

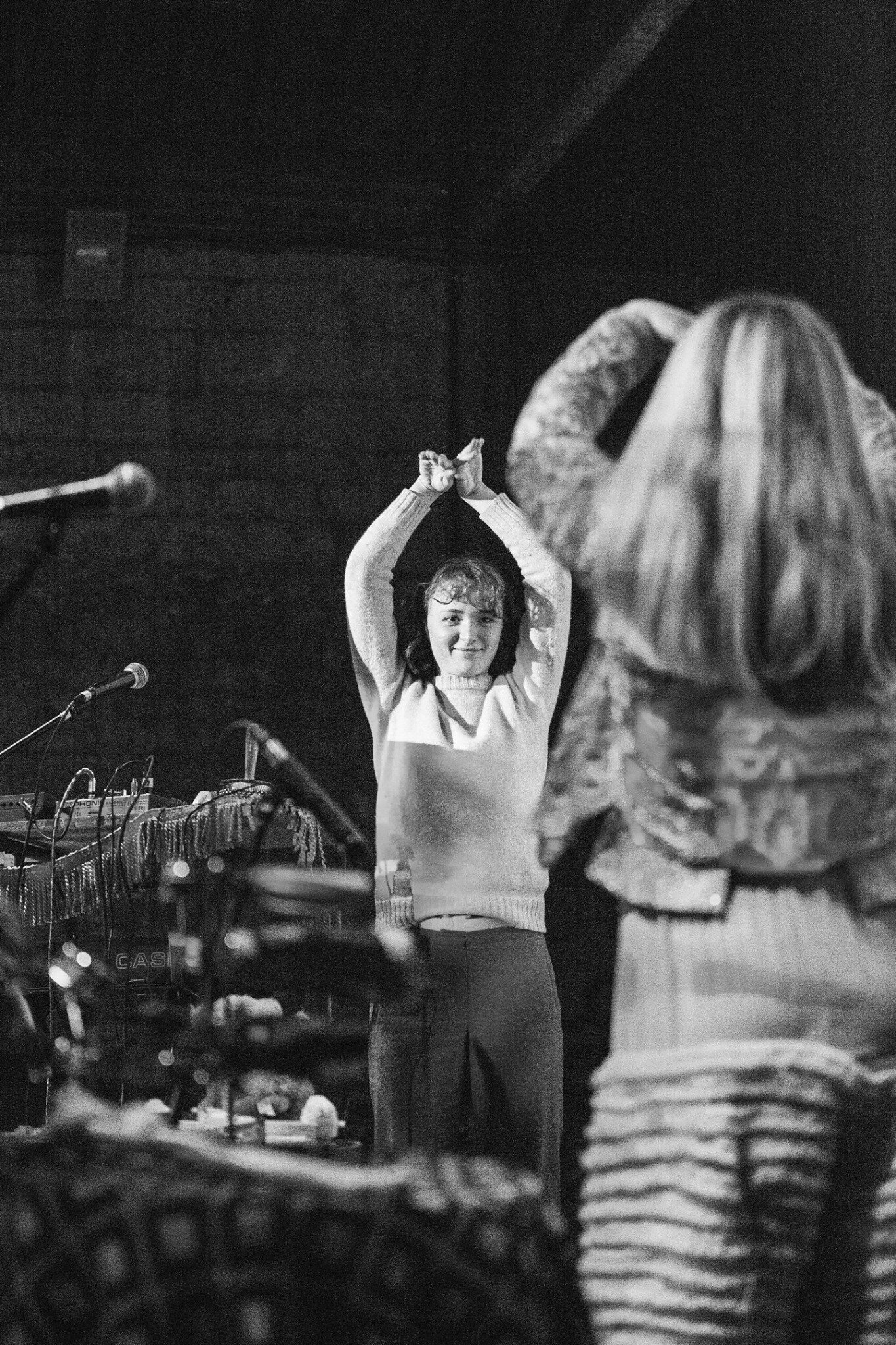

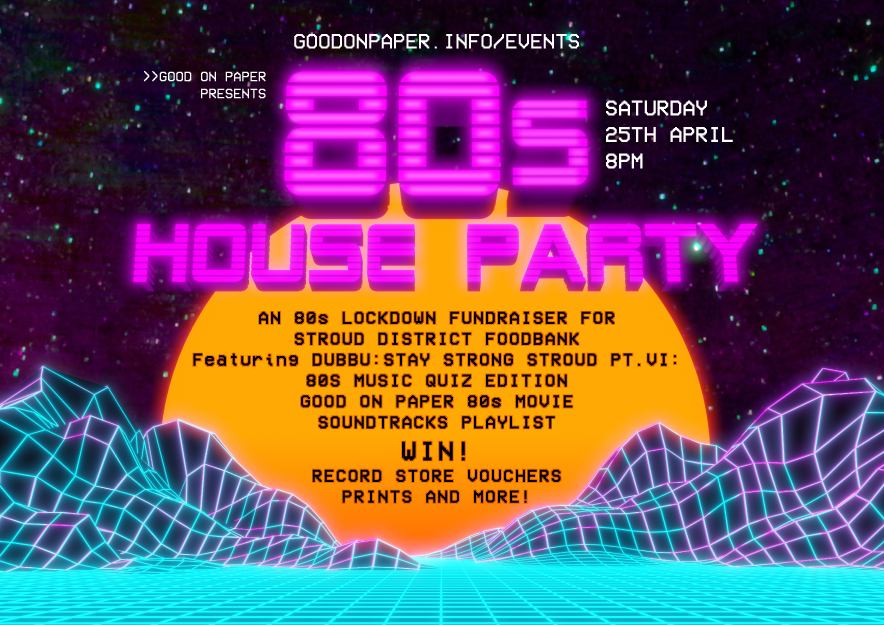

Emily Barker's shows have become increasingly Tennessee tinged in recent years. 2016 saw the Stroud-based Australian musician bring her country trio Applewood Road home for three beautiful sets. Two were at the Prince Albert, and the third at St Laurence's church - a setting that rendered the three-part harmonies of Barker and her Nashville-dwelling band-mates Amy Speace and Amber Rubarth all the more heavenly.

If you caught her solo show at the Albert last October, you'll have heard her duet with the lovable folk-punk rocker Austin Lucas, who she'd prised away from Nashville for a European tour. And all the while, she was getting ready to release her Memphis soul album, Sweet Kind of Blue, which was recorded at the legendary Sam Phillips Recording Service - the vast studio Phillips designed following his success producing Elvis, Johnny Cash, Howlin' Wolf and many more. The album is finally out this month, and Barker's new sound, complete with Al Greene's horn section, is already a hit with the critics.

Barker's first visit to a hallowed old American studio was across the state line from Tennessee, in Alabama. When visiting Nashville a few years ago, she recalls, "I drove down to Muscle Shoals and went to Fame studios... and it was just amazing. Aretha Franklin is one of my inspirations and she recorded there, and Etta James, so many legends and seeing this old equipment..." It was love at first sight.

As luck would have it, when considering producers for the new record, she was introduced to the Grammy-winning young Memphian sound engineer and producer Matt Ross-Spang. He cut his teeth at the late Sam Phillips' original shop-front studio, Sun, and had recently made his base at Sam Phillips Recording Service. "In America, we don't have ancient churches and castles like you do in Britain," says Ross-Spang, "but we have studios like this that to me are our version of those churches and castles. This place is just like walking into Phillips' brain."

And so last June, Barker headed to Phillips' Tennessee cathedral of sound, with little more than her beautiful 1937 Gibson acoustic guitar and a sheaf of new songs. Invited along for the ride, I arrive just as Barker pulls in for her first day of sessions. "I can't believe it's today - I'm so excited!" she says, smiling broadly under the warm, Southern sun. Sam Phillips' son Jerry, and granddaughter, Halley have swung by to welcome Barker. Unlike Sun, and Stax Records across town (Otis Redding, Booker T and the MGs and Isaac Hayes), this studio hasn't been made into a museum. The tapes have continued to roll here since 1960, which makes the private tour all the more spine tingling. Upstairs there's a tiny bar room with spirographic wallpaper, an atomic light and Johnny Cash's cigarette burns on the Formica counter. "Nothing in here has changed," says Halley. "Elvis, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, uhuh, they'd all come and sit here and drink, same stools and everything. Crazy huh?" The white furnishings and red shag carpet in Sam's old office still look brand new, and the sofa that sits outside it is off being restored by rock god and former upholsterer, Jack White.

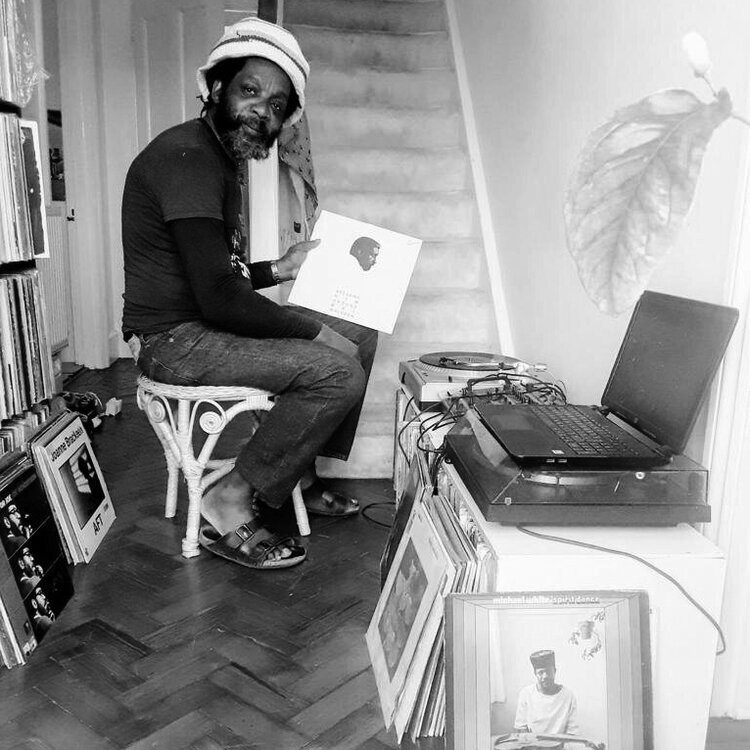

Downstairs in Studio A, a group of Memphis' finest musicians (many of whom played on Cat Power's record, the Greatest) have assembled. The studio is largely as it was when the Yardbirds recorded Train Kept A Rollin there in the early '60s. There's the same old Hammond organ, Jerry Lee Lewis' session piano and the original cigarette machine (just 75 Cents a pack).

Ross-Spang is riding high after his success with Something More than Free by Jason Isbell (who hails from Muscle Shoals and is a former member of Drive By Truckers) and Midwest Farmer's Daughter, the breakthrough album from outlaw country singer Margo Price. When he is done arranging microphones and cables he declares: "Hot diggety dang we just about ready."

Each take is counted in by drummer Steve Potts, who has played with Booker T and the MGs and Neil Young. "No one else drums like him," says Ross-Spang. "He's so laid back that it makes the whole song sway in this beautiful way. You just can't teach that." Fittingly, Potts' count in is the first thing you hear on the finished album, having been kept on the title track.

Over the coming days, as the band works through Barker's 11 songs, the mutual respect in the room swells to bursting point. Guitarist Dave Cousar tells Barker a few songs in: "your voice is like an iceberg," because every day he hears her do something new and surprising. By day four it feels like they've all known each other for years. When they've found their collective groove for the new song, If We Forget to Dance, Ross-Spang can't tear himself away from the studio floor. "This is some baby-making music," he says, and starts adding his own percussion, drumming the back of a guitar. At some point, Barker struts out of her vocal booth to put lipstick on the bassist, Dave Smith. And the road-trip song Sunrise ends in a spontaneous ten-minute jam, with Barker on mouthorgan.

Low lighting sets the mood for other tracks, and emotions flow accordingly. During a break from No. 5 Hurricane (which Couser describes thusly: "two words: Quentin. Tarantino.") Barker breathes: "I was getting tingly again." To which Rick Steff, on keys responds, "I was tearing up there for a minute."

"All the session guys," Ross-Spang tells me when the record's finished, "it wasn't just a normal session for them. They've all been calling me and texting me about just how wonderful it was for them. A really great moment I think for all of us."

A Sweet Kind of Blue is out now, available on-line and from all good independent records stores. Visit emilybarker.com for further info.

Amy Fleming is a writer and editor for the Guardian, who also contributes to Intelligent Life, the FT, Vogue, Newsweek, New Scientist and more.