By Paul Harper

Issue 38, May 2018

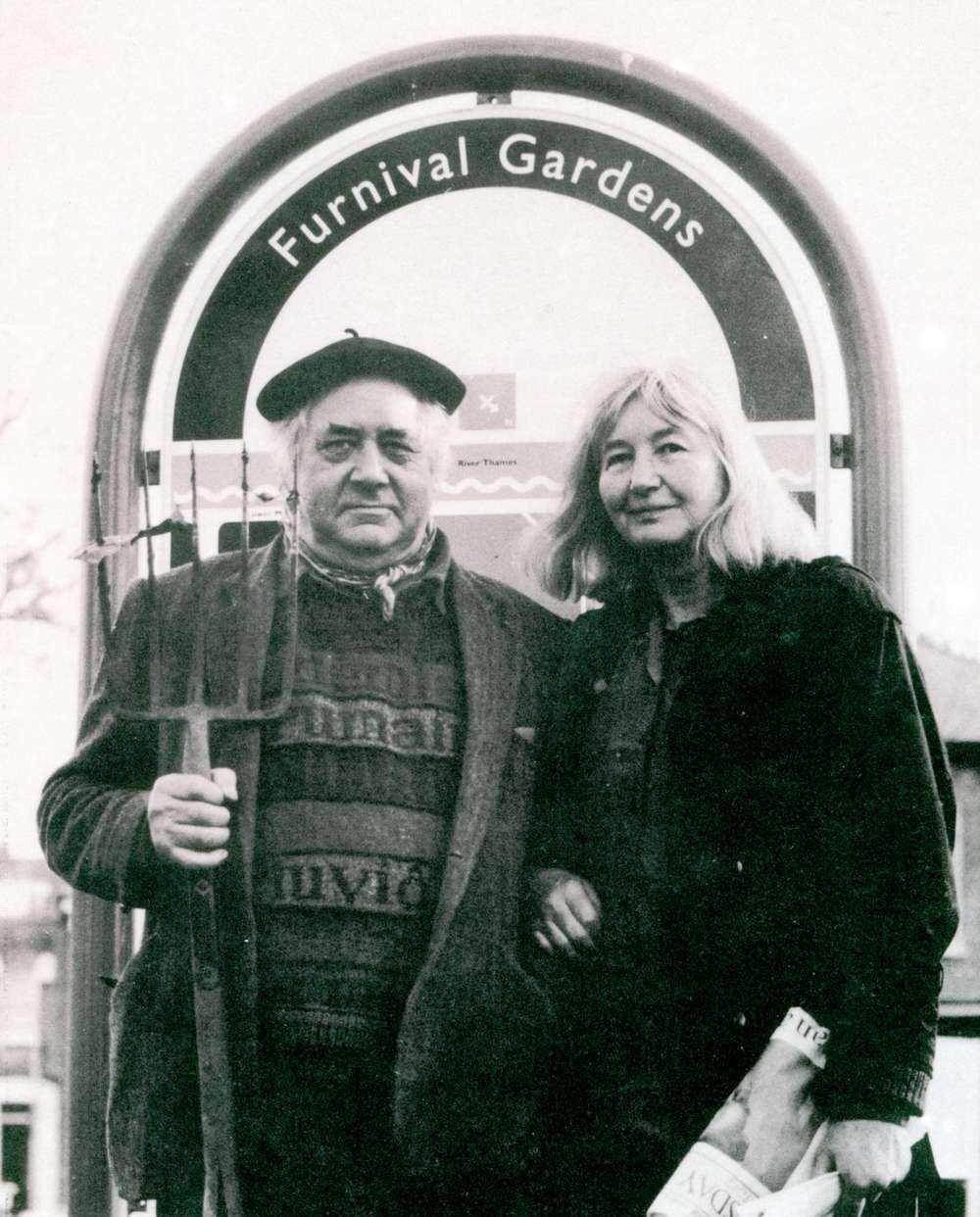

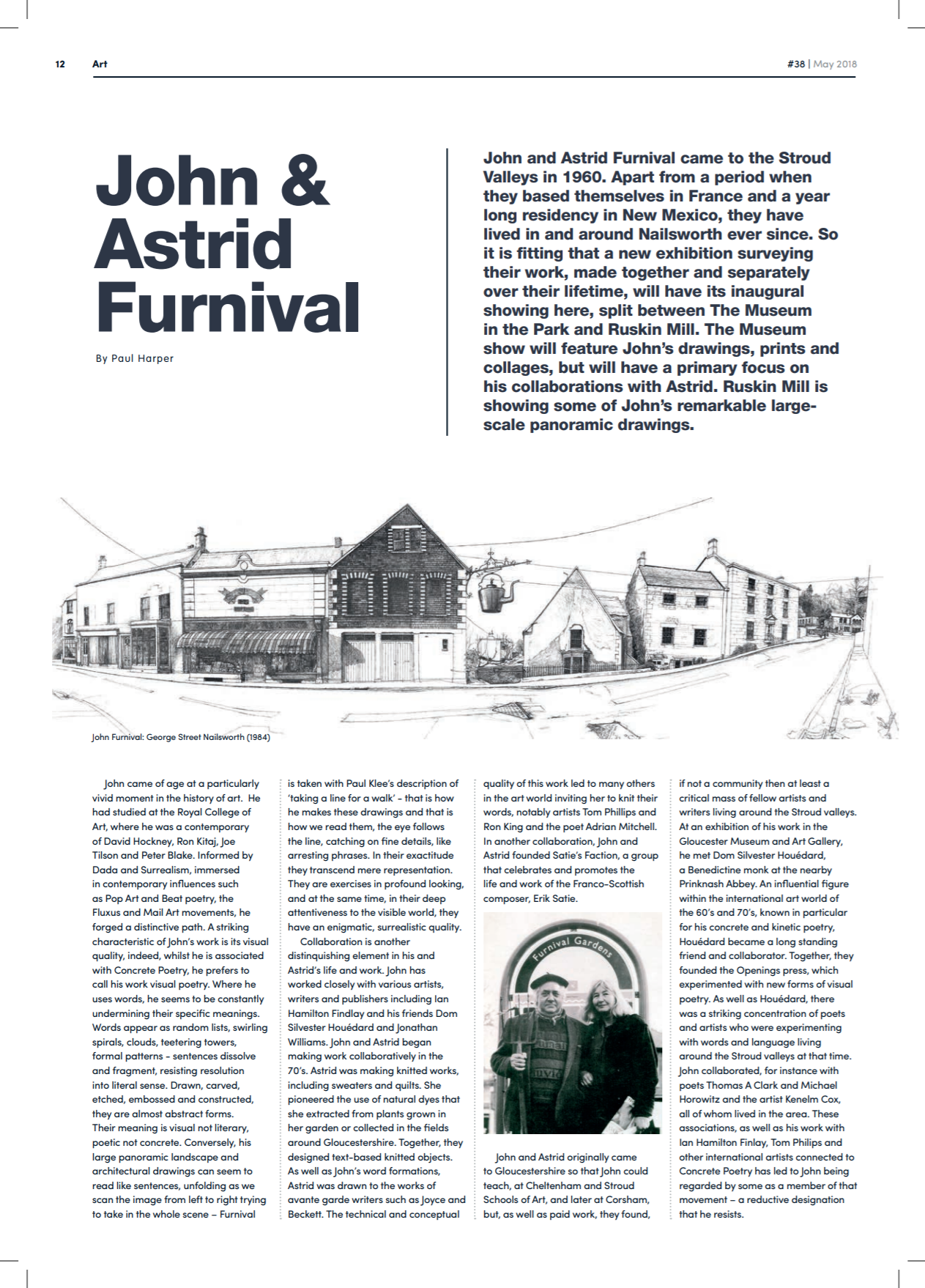

John and Astrid Furnival came to the Stroud Valleys in 1960. Apart from a period when they based themselves in France and a year long residency in New Mexico, they have lived in and around Nailsworth ever since. So it is fitting that a new exhibition surveying their work, made together and separately over their lifetime, will have its inaugural showing here, split between The Museum in the Park and Ruskin Mill. The Museum show will feature John’s drawings, prints and collages, but will have a primary focus on his collaborations with Astrid. Ruskin Mill is showing some of John’s remarkable large-scale panoramic drawings.

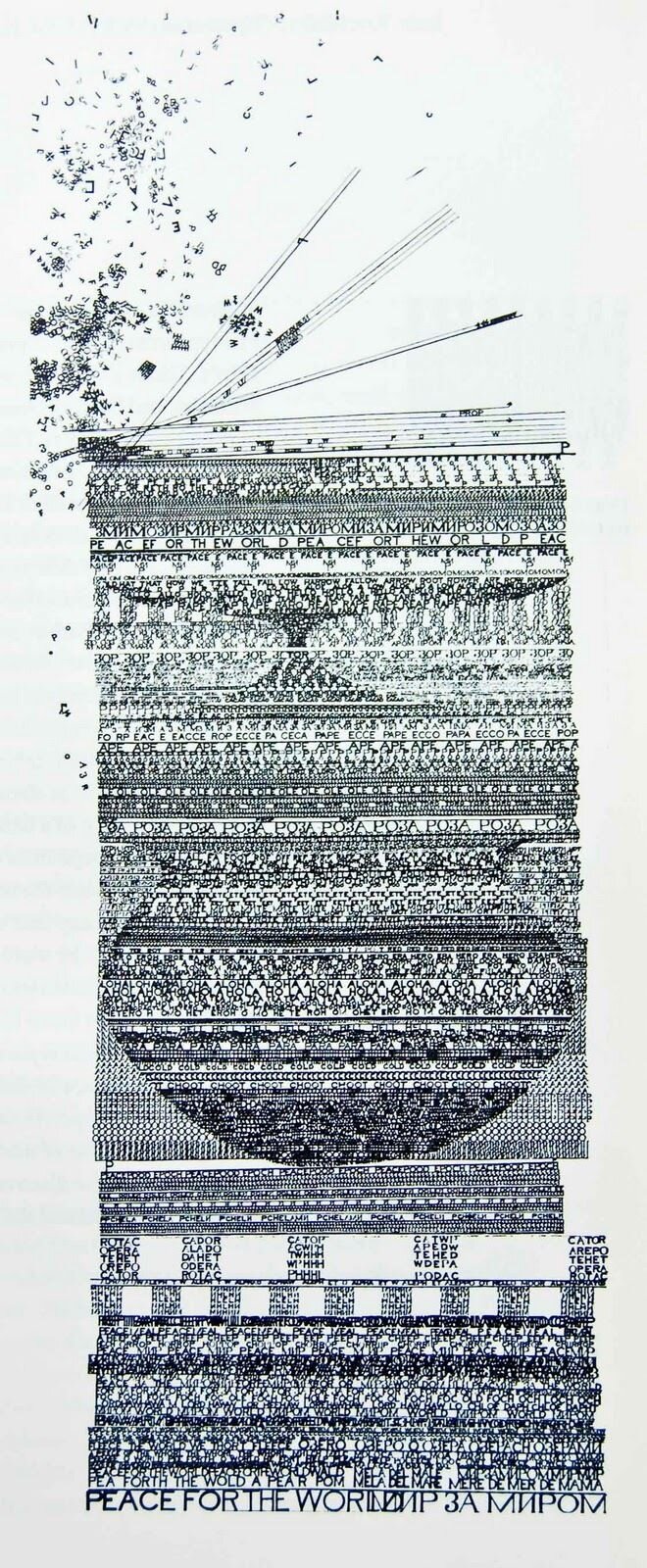

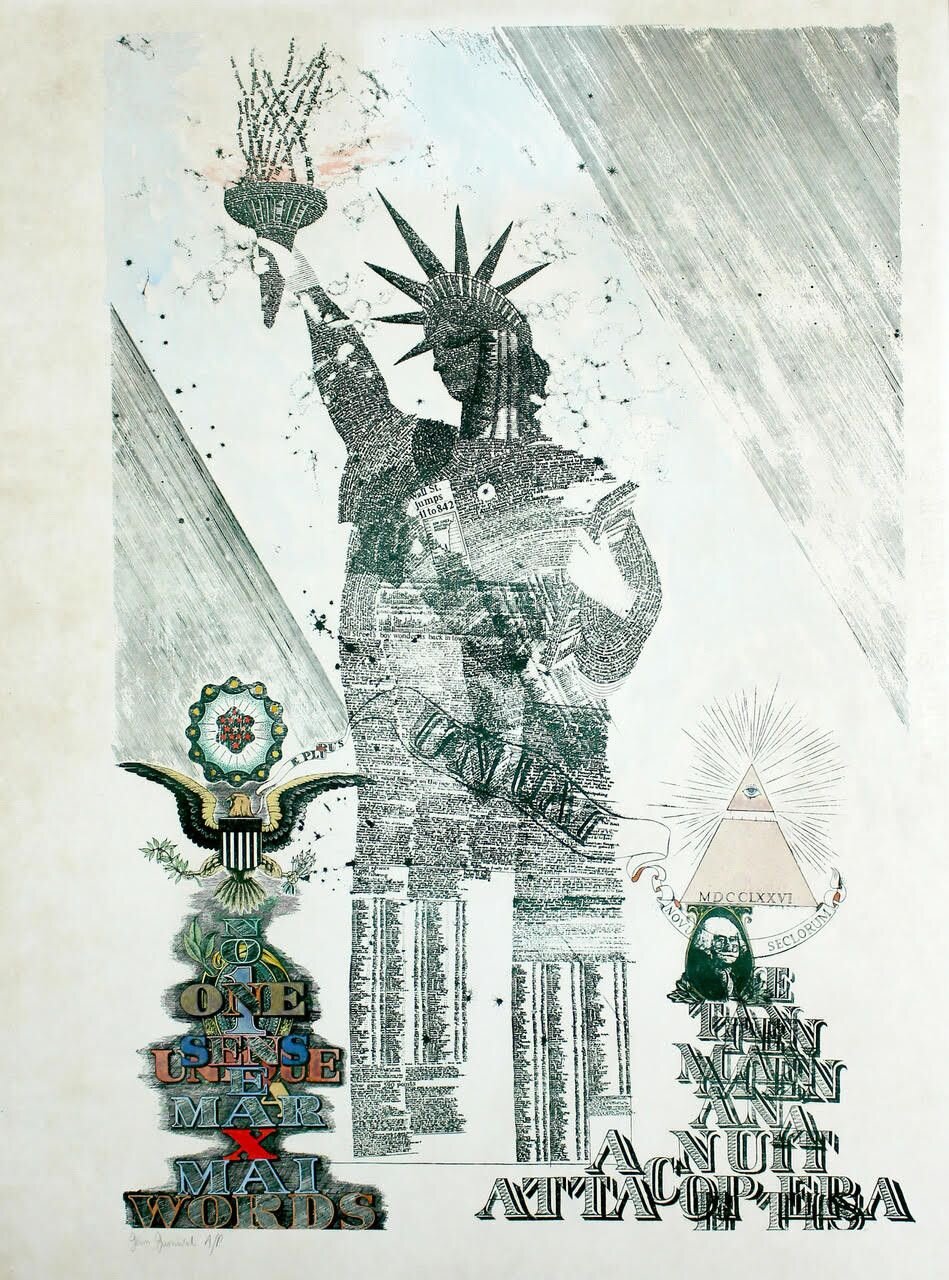

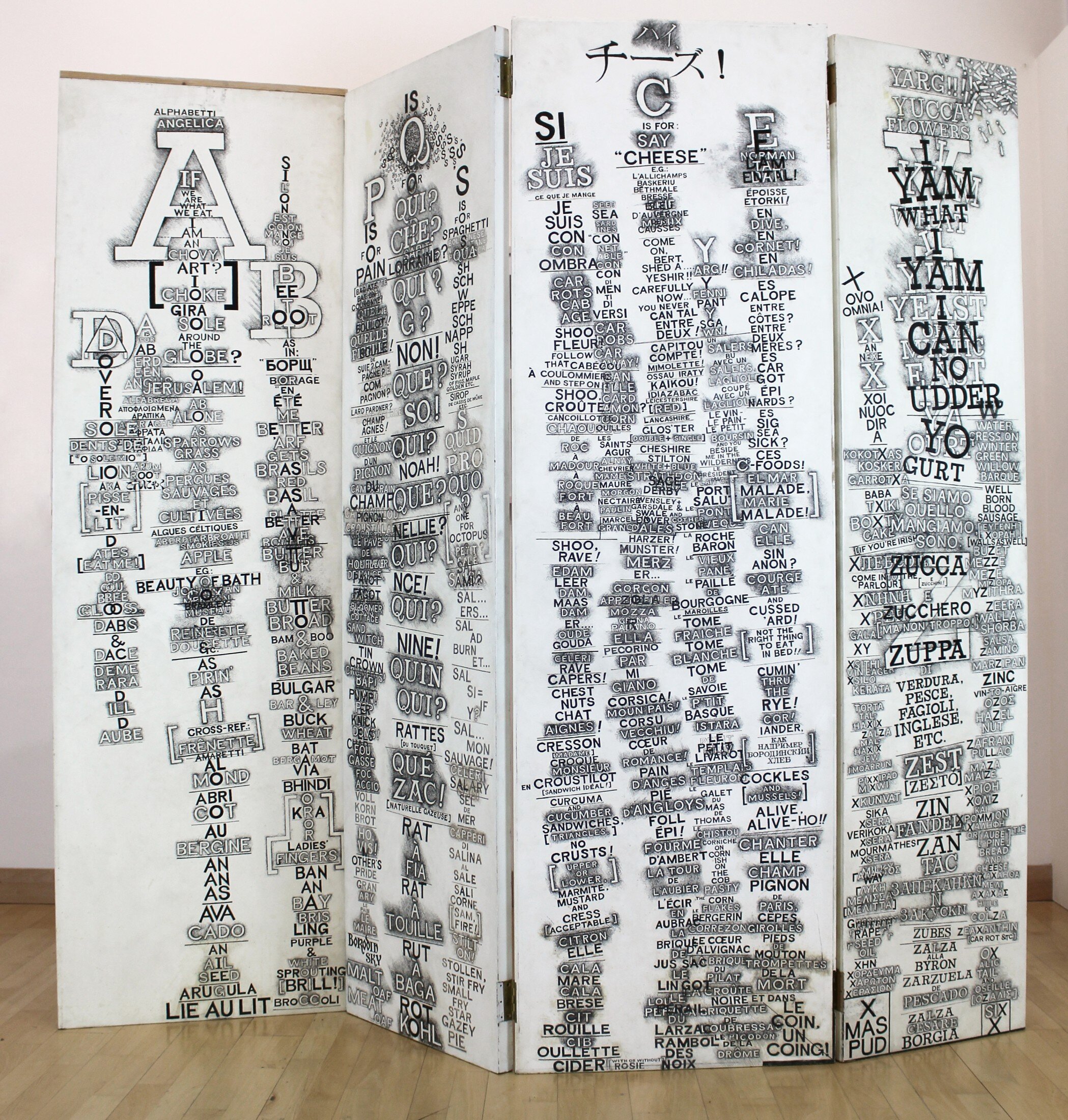

John came of age at a particularly vivid moment in the history of art. He had studied at the Royal College of Art, where he was a contemporary of David Hockney, Ron Kitaj, Joe Tilson and Peter Blake. Informed by Dada and Surrealism, immersed in contemporary influences such as Pop Art and Beat poetry, the Fluxus and Mail Art movements, he forged a distinctive path. A striking characteristic of John’s work is its visual quality, indeed, whilst he is associated with Concrete Poetry, he prefers to call his work visual poetry. Where he uses words, he seems to be constantly undermining their specific meanings. Words appear as random lists, swirling spirals, clouds, teetering towers, formal patterns - sentences dissolve and fragment, resisting resolution into literal sense. Drawn, carved, etched, embossed and constructed, they are almost abstract forms. Their meaning is visual not literary, poetic not concrete. Conversely, his large panoramic landscape and architectural drawings can seem to read like sentences, unfolding as we scan the image from left to right trying to take in the whole scene – Furnival is taken with Paul Klee’s description of ‘taking a line for a walk’ - that is how he makes these drawings and that is how we read them, the eye follows the line, catching on fine details, like arresting phrases. In their exactitude they transcend mere representation. They are exercises in profound looking, and at the same time, in their deep attentiveness to the visible world, they have an enigmatic, surrealistic quality.

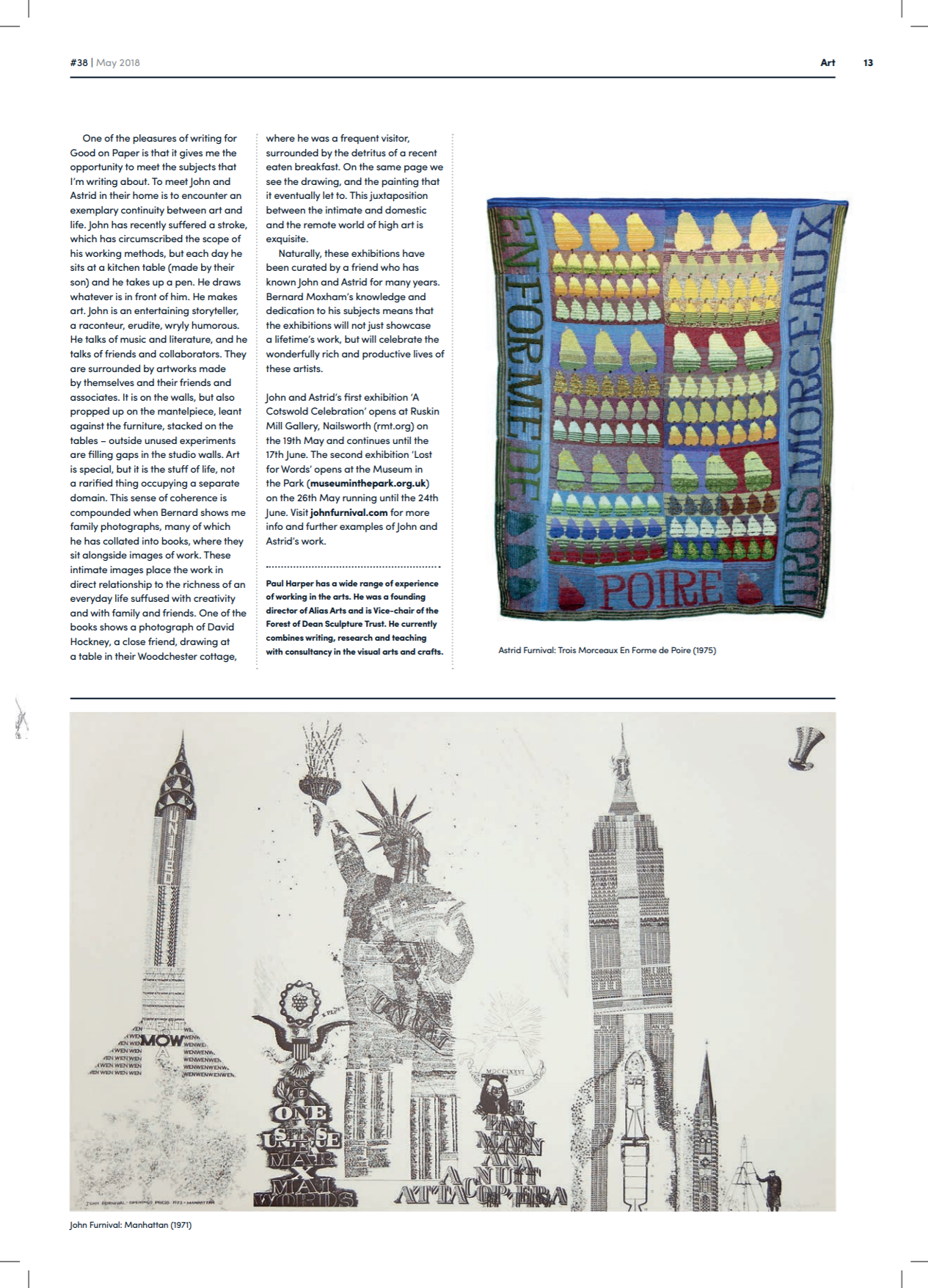

Collaboration is another distinquishing element in his and Astrid’s life and work. John has worked closely with various artists, writers and publishers including Ian Hamilton Findlay and his friends Dom Silvester Houédard and Jonathan Williams. John and Astrid began making work collaboratively in the 70’s. Astrid was making knitted works, including sweaters and quilts. She pioneered the use of natural dyes that she extracted from plants grown in her garden or collected in the fields around Gloucestershire. Together, they designed text-based knitted objects. As well as John’s word formations, Astrid was drawn to the works of avante garde writers such as Joyce and Beckett. The technical and conceptual quality of this work led to many others in the art world inviting her to knit their words, notably artists Tom Phillips and Ron King and the poet Adrian Mitchell. In another collaboration, John and Astrid founded Satie’s Faction, a group that celebrates and promotes the life and work of the Franco-Scottish composer, Erik Satie.

John and Astrid originally came to Gloucestershire so that John could teach, at Cheltenham and Stroud Schools of Art, and later at Corsham, but, as well as paid work, they found, if not a community then at least a critical mass of fellow artists and writers living around the Stroud valleys. At an exhibition of his work in the Gloucester Museum and Art Gallery, he met Dom Silvester Houédard, a Benedictine monk at the nearby Prinknash Abbey. An influential figure within the international art world of the 60’s and 70’s, known in particular for his concrete and kinetic poetry, Houédard became a long standing friend and collaborator. Together, they founded the Openings press, which experimented with new forms of visual poetry. As well as Houédard, there was a striking concentration of poets and artists who were experimenting with words and language living around the Stroud valleys at that time. John collaborated, for instance with poets Thomas A Clark and Michael Horowitz and the artist Kenelm Cox, all of whom lived in the area. These associations, as well as his work with Ian Hamilton Finlay, Tom Philips and other international artists connected to Concrete Poetry has led to John being regarded by some as a member of that movement – a reductive designation that he resists.

One of the pleasures of writing for Good on Paper is that it gives me the opportunity to meet the subjects that I’m writing about. To meet John and Astrid in their home is to encounter an exemplary continuity between art and life. John has recently suffered a stroke, which has circumscribed the scope of his working methods, but each day he sits at a kitchen table (made by their son) and he takes up a pen. He draws whatever is in front of him. He makes art. John is an entertaining storyteller, a raconteur, erudite, wryly humorous. He talks of music and literature, and he talks of friends and collaborators. They are surrounded by artworks made by themselves and their friends and associates. It is on the walls, but also propped up on the mantelpiece, leant against the furniture, stacked on the tables – outside unused experiments are filling gaps in the studio walls. Art is special, but it is the stuff of life, not a rarified thing occupying a separate domain. This sense of coherence is compounded when Bernard shows me family photographs, many of which he has collated into books, where they sit alongside images of work. These intimate images place the work in direct relationship to the richness of an everyday life suffused with creativity and with family and friends. One of the books shows a photograph of David Hockney, a close friend, drawing at a table in their Woodchester cottage, where he was a frequent visitor, surrounded by the detritus of a recent eaten breakfast. On the same page we see the drawing, and the painting that it eventually let to. This juxtaposition between the intimate and domestic and the remote world of high art is exquisite.

Naturally, these exhibitions have been curated by a friend who has known John and Astrid for many years. Bernard Moxham’s knowledge and dedication to his subjects means that the exhibitions will not just showcase a lifetime’s work, but will celebrate the wonderfully rich and productive lives of these artists.

John and Astrid’s first exhibition ‘A Cotswold Celebration’ opens at Ruskin Mill Gallery, Nailsworth (rmt.org) on the 19th May and continues until the 17th June. The second exhibition ‘Lost for Words’ opens at the Museum in the Park (museuminthepark.org.uk) on the 26th May running until the 24th June. Visit johnfurnival.com for more info and further examples of John and Astrid’s work.

Paul Harper has a wide range of experience of working in the arts. He was a founding director of Alias Arts and is Vice-chair of the Forest of Dean Sculpture Trust. He currently combines writing, research and teaching with consultancy in the visual arts and crafts.

As well as our recent project (Good On Paper TV) following Good On Paper’s current hiatus over the next few month’s we will be putting up articles from our archives for our readers to easily access and share…Community and culture can carry on in different ways. For now….