By Paul Harper

Issue 57, December 2019

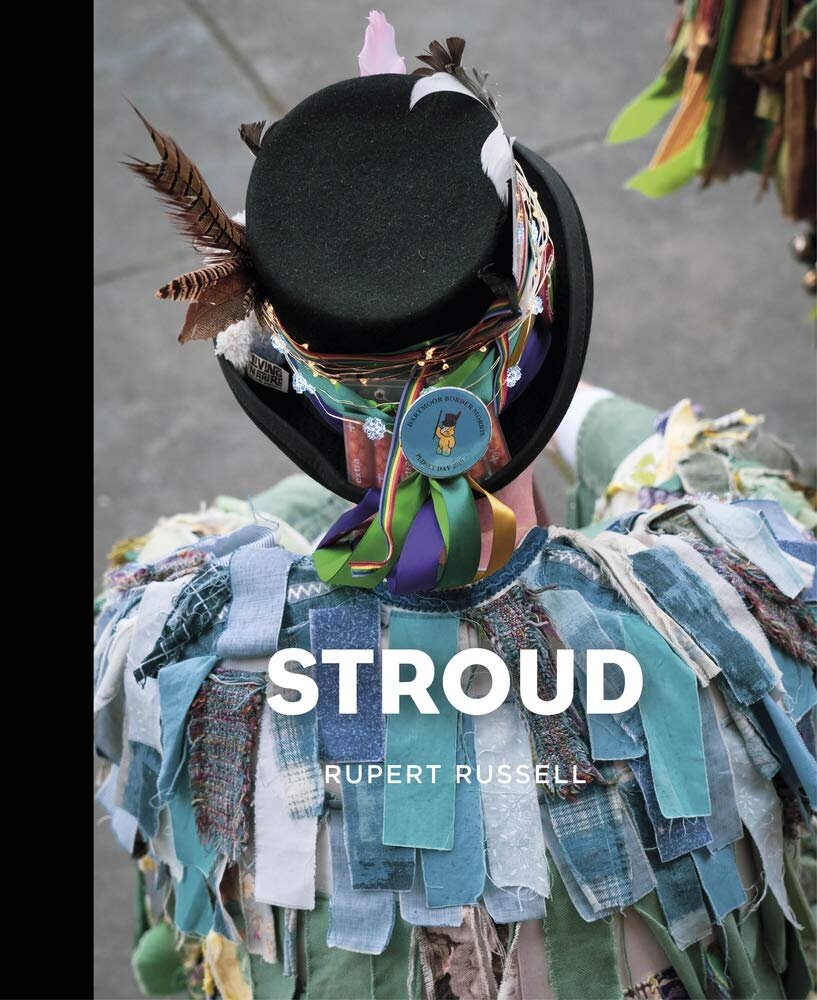

Rupert Russell, whose excellent book of street photography is being published this month by the History Press, has come to photography relatively late in his life.

He has had a number of other careers, as an actor and as the proprietor of his family’s dry-cleaning business, previous to taking up his camera in a serious way. It was only when he turned 40 and began to photograph his recently born first child that he committed himself to learning more about the medium and to developing his skills. Having made that shift, he now has a thriving professional practice, which includes a passion for sharing his knowledge and experience with others as a teacher as well as running a commercial studio.

Although Rupert has little formal training, he has always been interested in photography, attracted initially by the technical discipline and by his fascination with the precision engineering of the camera as much as the creative possibilities. He claims to lack patience, preferring the speed of the digital to slow traditional, analogue processes. If this sounds like a dry, techie interest, he also talks about the joy of taking pictures. As he talks, what he describes as impatience begins to seem more like excitement with the rapid feedback of the digital process, the way that working quickly sharpens the senses and allows a certain responsiveness that can lead to happy accidents. His interest in the camera as an object evokes the allure that all tools have for the craftsman. Rupert is enthusiastic about the immersive process of making and printing an image, and he talks about photography as a way of looking at, and connecting with, the world. As he puts it himself “My love for photography is driven by a desire to connect with people and the environment - all the wonderful things with whom I share this astounding planet. I gain a deep satisfaction, both intellectually and emotionally, when I take pictures.”

Being commissioned to produce the book, entitled simply ‘Stroud’, is a kind of validation for Rupert’s identity as a photographer as well as a celebration of the place where he grew up and made his home. The brief was open – to capture the unique qualities of the town and to get under the skin of the people. His own sense of Stroud is as a refuge in the eye of a storm; a home to a radical tradition; a place where people make things happen; a place that is open and tolerant; a bit of dirty realism set within the staggering beauty of the five valleys and the Cotswold Hills. It is clear that the book has been a labour of love.

None of the images are staged. He wants to capture people in the moment, using only natural light. He has to be observant and spontaneous, and he has to be adept at approaching his subjects in such a way as to make an authentic image that reveals something of their personality. The results are naturalistic, and unforced. What is striking in all the photographs is the sense of place. Rupert limited himself largely to the pedestrianized centre of the town. The locations are familiar, not always chosen for their picturesque qualities and unmistakably Stroudie: the Corn Exchange, the laundrette at the top of the High Street, Bank Gardens, the commons, glimpsed between the rooftops of the townscape.

Whilst the settings are distinctly present in the image, the focal point is always the people, picked out for their character and the way that they project a sense of imminent story, of an unfolding event, rich with narrative possibility: a woman stands with an air of anticipation on the steps of the Sub Rooms; a boisterous group of young people strike a pose in the Church Yard; a man waits with weary resignation for his washing to finish in the laundrette. Whilst many of the images are taken on the hoof as it where, snatched as they stand, Rupert will sometimes elicit a direct response from his subject. One strategy that he uses is to ask them a question, “… do you feel loved?” They look directly into the camera – thoughtful, defiant, melancholic, amused. All of the photographs are suffused with affection – for the town and the people.

Rupert points out that, in a sense, we are all photographers now, documenting our lives with our mobile devices. We record the prosaic details of our daily existence on our smartphones and construct our identities on Instagram. The photographic image is so profuse and commonplace that it is easily overlooked. In Rupert’s book our attention is caught by the particularity of the settings and the vivid characters, and then we’re drawn to look closer at a familiar world, to see it through a fresh lens.

Stroud, by Rupert Russell, is out now published by The History Press (thehistorypress.co.uk) Visit rsdrphoto.co.uk for further information and examples of Rupert’s work.

Paul Harper has a wide range of experience of working in the arts. He was a founding director of Alias Arts and is Vice-chair of the Forest of Dean Sculpture Trust. He currently combines writing, research and teaching with consultancy in the visual arts and crafts.